Pluralism and Apocalypse

A Teleology of Tradition

For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then I shall know even as I am known.

1 Corinthians 13:12

(Part three, then. The first post was a discussion of the borders of tradition. The second was an attempt to hone in on the role and nature of the sacred text in particular. As a preface to the third: I have mulled over this topic a great, great deal (hence the inordinate amount of time it has taken me to publish it) and am especially grateful to Jack and Christian for their motions to push back against the bolder renderings of this thesis. At a certain point, I am inclined simply to say ‘I don’t know’. I find that to be wisest. In fact, I actually find it especially apposite that I have found my own position so troubled, because it is precisely at that point of wordless quiet, where our rational discussions and positions must cease, that I believe religion (and, slightly more locally, this mini-series) should end. So permit me to work things out in writing, and offer a few opinions which may very well be hopelessly wrong).

THOUGH by no means a doctrinaire Aristotelian, I do take some of his principles to be self-evident. For instance: if you want to understand anything, you cannot fail to look to its purpose. The teleology of religion is incidentally one of its most unifying features in an otherwise confusingly variegated field: an overwhelming majority of faiths are oriented toward a notion that might generally be rendered ‘salvation’, a deliverance from present suffering into perpetual bliss. However, the impression one generally receives of many religious traditions—especially those of the Abrahamic variety—is that they understand themselves to be an exclusive reserve of divine revelation and by extension salvation, that if there is any merit to other traditions it is in their pale imitation of that Truth of which ‘we’ are possessed in its fullness. They may have an inkling, but we have the whole story. Their Scriptures are corrupted, whilst ours are impeccable. Their devotion is misguided or idolatrous, whilst our deity is supreme. And, vitally, what this means at the crucial moment is that humanity will finish its story divided: it will be ‘us’ and ‘them’ for eternity. All this creation is a competition, and there will be winners and losers. And we, of course, will win.

The logic I have invoked throughout this brief series is concerned with the often peculiarly rendered relation between unity and difference. Particular traditions and Scriptures are claimed to possess complete revelation from the Source of all reality, and yet this is a fairly top-heavy claim, to say the least. To reprise a previous example, it is like an elephant sitting on a tricycle; or, better, like the universe itself sitting on the head of a pin. Or, better still, taking even that image and expanding it beyond infinite proportions, as there is no quantitative ratio between God and world, let alone any part of that world, that might suggest he could in any way be ‘limited’, penned in by the four corners of a book or the slightly more intangible borders of a religious community or tradition.

If we begin with ends (‘teloi’), we find ourselves faced by the first of a handful of problems associated with ‘pluralism’, or simply comparative religion in general. This is, as I indicate, soteriological in nature, and one I happen to take as relatively rather easy to answer. A fuller universalism post is sitting in draft, so I do promise to elaborate, but en bref I will say that universalism seems to me a necessary corollary of the belief in a universal Creator, the Being in which all particular beings—irrespective of their diversity and contrast—live, move, and have their being (Acts 17:28). Any positing of an eternal difference along doctrinal lines is clearly a division interior to a yet more foundational unity, and so one that cannot be ultimately binding on that unity. And more specifically, in equating salvation with the mere affirmation of a particular creed, we reduce that salvation to a spiritual shibboleth rather than a state of soul. Hence the truncated, almost infantile soteriology of common parlance: if you’re in the club (having said the special words, done the special rituals, been invited into the secret treehouse meetings), then you’re going to the good place; if you’re not, then it’s best not to talk about where you’re going.

My objection to this is that it signifies a blatant dualism, and (as I say) a conflation of a foundational unity with its own interior distinctions: a category error for which the best analogy is the belief that two bellicose movie characters might somehow, in their violence, tear a fissure in the cinema screen itself. It cannot be the case that God or Ultimate Reality—whose experience or union is typically thought of as this ‘salvation’—is finally ‘articulated’ in any particular formulation of faith or creed, because that would be to reduce him to a mere being amongst beings, something totally intelligible and so requiring a yet larger horizon of intelligibility in which to situate it: and so to render Him not God. I would think that all but the most obtuse fundamentalist would admit that God is not something exhausted, rather only signified by, a creed or text or person—and at that point, we would have to seriously ask ourselves whether the fundamentalist is even talking about ‘God’ at all, rather than a fancifully conjured pater familias who works just for them and no one else, and occasionally deigns to the playground to beat up the other kids: in short, to reduce religion as a whole to ‘my Dad’s bigger than your Dad’.

But I digress. I am only delaying—or prefacing, if you are charitable—the real problem. Yes, many a pious book-basher would take immense issue with what I have just said, it being a bare-faced endorsement of monism and universalism. But despite their controversy, I take these issues to be the low hanging fruit. Again, I think them to be obvious corollaries of classical theism, and anything to their contrary I struggle to see as in any way a coherent metaphysics, rather than what they must be: some deflated husk that collapses dolefully into mere tribal allegiance (no matter the smells and bells of your rite, or the hefty weight of gold in the institutional bank). What is actually the more pressing topic, and the far more difficult one to navigate—where, specifically, my brow starts to furrow and my mind gives way to radio static—are the thornier problems of pluralism, problems which extend beyond mere soteriology. One may well be a universalist or a monist, but that does not entail the ‘truth’ of pluralism. Both of those positions may be perfectly amenable to an inclusivist of the most condescending colonial ilk, or even an exclusivist who believes all will simply come to ‘see the light’ of their own position in the fullness of time.

If we begin the pluralistic debate with something along the lines of ‘Are all religions true?’ or ‘Can more than one religion be true?’, I would begin by avoiding the question altogether. It rests, after all, on what I take to be a clearly defunct epistemology. We tend to enagage such discussions as though we were already in agreement that what we are referring to when we talk about ‘religions’ is a set of clearly delineated monads. In reality, the beginning and end of the magisterium of a given tradition is a protean and thoroughly negotiated demarcation, changing incessantly throughout the course of history. The ancients had a better grasp of this: the Latin term religiō by no means referred to an enclosed, isolated entity, distinctively cut off from other ‘religions’; rather, it referred to something more akin to a virtue or way of life, not a girdled propositional system to which one generally subscribes. Subsequently ‘syncretism’, as one author puts it, ‘happens’.1 It is not an insidiously subersive option for the unchastened heretic, nor merely a convenient tool for the missionary attempting to evangelise in foreign lands. Syncretism is simply what religion is. Human habit, as Schelling or Bergson would tell us, is to abstract the ever-moving world into inert, quantifiable concepts or atoms in order to make sense of things. This is both useful and acceptable, so long as we do not do precisely what modernity does: read these dead entities back into the world as though they were objective realities. Little wonder our contemporary religious thinking fits so well with the modern economic paradigm of late-stage capitalism. It is supposed that the venerable wisdom traditions sit pretty like differing candy flavours under the head-throbbing industrial light of some Walmart aisle, an array of saccharine confectionaries for the disinterested, perfectly poised consumer (‘free thinker’?) to pick between.

Contrary to this dilapidated consumerism, as practically every major religious writer influenced by Plato attests, we are drawn to God not simply as one is drawn to a particular product. God is that which is desirable in Himself, which stands in contrast with every worldly desideratum, each of which promise only a limited satiety and inescapable unfulfilment, being only imitations of an infinitely satisfying End. The classic ‘transcendentals’ of goodness, truth, and beauty, all of which humans are naturally drawn to, converge upon the infinite horizon of their unity in God. Contrary to the consumerist picture, there is really no motion of desire or attraction—no act of rational intention, directing the mind toward a particular logical, ethical, or aesthetic end—that is not in some way simply a small ‘segment’ or ‘interval’ bracketed from an ultimate fullness of which one is already really possessed, but which must only be realised. As Gregory of Nyssa says,

Denuded and purified from all these [materialistic impulses], our desire will turn its energy towards the only object of will and desire and love. It will not entirely extinguish our naturally occurring impulses towards such things, but will refashion them towards the immaterial participation in good things.2

As such, I am not remotely persuaded by the modern model that looks to gather up the whole of Christianity in a bundle, push apart some equally ill-defined collation of Islam, and then lucidly compare the two separate cohorts as though they were simply logical propositions or mathematical formulae, independent of the subject. This is an abstraction of an abstraction, at best. It first removes itself from the reality of shifting, syncretistic religious borders, and then removes itself again from the reality of religion as a lived experience rather than—well, an abstraction.

What this means is that when we do consider those very real decisions made by people not in abstract but ‘on the ground’ (even as elementary as whether one goes to the masjid or synagogue to worship) we are not merely entering the ‘religious sphere’ as a subject separate from its object. Desire itself, in all its forms, is at least latently if not manifestly religious. Not just desire in fact, but if we posit our monism then everything is God, seen more or less clearly. All that religion is, in this understanding, is the process of clarifying one’s vision to register this. With both this and the reality of syncretistic borders in mind, we problematise the ‘consumerist’ vision of religious difference and collapse it instead into life itself. Religion is not other to life; even the supposedly secular sphere is littered with rituals, doctrines, and teleologies of its own, albeit of a generally deficient and shamefully disenchanted, materialistic sort. The premises of classical theism simply do not allow for a coherent ‘irreligiosity’ because they identify God with the most foundational acts of conscious existence.

To further distance ourselves from consumerism: when scholars assert that religion is a historical phenomenon, this should not be interpreted as mere sociological reductionism. It should, rather, be understood as the basic assertion that religions are irreducibly grounded in and produced by all those particular lives, cultures, and civilisations through which they have played out during their history. We can trace theological developments to historical trends, occurrences, and people. Michael Sells’ beautiful translation of the earliest Qur’anic revelations (Surahs 1, 53, 81-114) is introduced by much-needed context surrounding the life of Muhammad, pre-Islamic Arabian paganism and civilisation, and the culture of the earliest and even contemporary Muslims. The Qur’an is littered with images reflecting the embodied reality of life under a harsh Arabian climate, and conversely configures ‘salvific’ images of jannah as constituted by ‘luscious gardens’ with ‘flowing springs’, ‘every fruit’ (Q 25:16) and foliage shade (Q 53:14-16). This is obviously not to say that the text’s value is simply in describing a given point of history: it speaks to something more metaphysical, through the conditioned and mutable historical milieu. Only that we must not forget that it is still very much historical, not floating pristinely above this interrelated complex. I argued against this impossibility in the previous post.

We can muse further on how all manner of contingencies, small and large, might have altered the entities we now cleanly separate as differing ‘religions’. How much of the life of Paul constitutes Christianity? And how much of that was because of his peculiarly melodramatic temperament, or his exposure to the esoteric grandeur of Merkavah mysticism, or the degree of woozy dehydration he might have felt as he set out on his way to Damascus? How seriously might Muhammad’s claims to prophecy have been taken if he did not suffer from epilepsy, or how susceptible might he have been to revelation without it? We know that one of the early threats that Christians felt of Islam was its successful imperialistic expansion across the Middle East: this, in the ancient world, generally signified divine favour, thus troubling and then altering Christians’ self-understanding as chosen people under the guide of providence. The trembling fingers of an eighteen year old boy in military camps the night before the Battle of Yarmuk, remembering the way their mother would cook their favourite dish, might suddenly be spurred in nostalgic love to an even greater desperation to survive, and so ensure Rashidun victory. Or, in a different universe, that same boy might have—under the oppressive Syrian heat—carelessly asked to sky the flask of a sickly stranger a few days earlier and then, having inadvertently infected the rest of the camp, tip the tide of that battle in favour of the Byzantines, thus potentially changing the face of human history and the way both Islam and Christianity and every other religion influenced by those two (which is practically all of them) understand themselves, and all preach their supposedly ‘exclusively true’ doctrine.

What I am getting at is that, contrary to the question which seeks to set them against each other, religions are not static essentialisms that may be exhaustively expressed in their propositions subject to the law of the excluded middle. Religions are not enclosed systems of logic, though systems of logic can and should obtain within religion. They are, rather, ever-shifting patterns of living; forms of comporting ourselves toward our End, habituated by rite, community, and art, constantly prodding us to turn ourselves to what life actually is.

Yes, there are particular truths in states of affairs that interact with and rule out other states of affairs in the world, and Christianity and Islam certainly are opposed in public discourse with the rigor of a logical problem because they have competing claims governed by the law of the excluded middle. Long may those debates continue. Jesus either did or did not physically turn water into wine; Muhammad either did or did not physically split the moon in half. Either Muhammad was the final prophet of God, or he was not. Either the Bible is corrupted, or it is not. But aside from the fact that some of these can already be problematised as mere dualisms, we are obviously speaking of a certain ‘transcendence’ being cited as justification for each. For any Muslim or Christian to debate any such proposition, both must be in tacit agreement that the ‘truth’ of the state of affairs exists, and it only remains to determine what that truth is according to the evidence. Propositions do not contain or exhaust the truth, but derive their veracity from it. And, to further the point, it should surely be apparent that neither religion is the mere totality of its propositional claims, for anyone could register epistemic accordance with a creed without actually being religious; if it has no effect on your manner of living whatsoever, belief in the historical resurrection or the revelations to Muhammad would make you nothing more than a non-naturalistic historian. That abstracted veneer of a coherent, identifiable, propositional whole which we might call ‘Judaism’ or ‘Sikhism’ or ‘Zoroastrianism’ can at most be employed as a useful point of entry to adopt a certain way of living. But never should the purchase of this ticket be thought to ensure the static, unmoving quality of the ride: surely quite the opposite.

What I am postulating is certainly the existence of determinate form in religion (because without that we would have unintelligible holism), but vitally that such determinate form need not and ultimately cannot in any meaningful way be set off against a similar determinate form. Just as I said in my post on Christian doctrine, ‘religion is not a historical theory’. In the same vein: religion is not an abstraction and so, ultimately, not something that can be subject to negation as an exhaustive whole. Anything that is thought—any cognitive belief one holds, whether that be ‘Jesus rose from the dead’, ‘There is one God and Muhammad is his Prophet’, or ‘The Jews are God’s chosen people’—is necessarily a contraction of one’s being, a particular, determinate occurrence within a broader fabric. To reuse my earlier analogy, all the conflicts and discordances of movie characters appear on a unifying screen, and nothing of their difference, however significant, could ever effect that screen. To live is to live in God, and just as two human lives can be absolutely distinctive whilst neither fails to be any less ‘true to life’, so too the same can be thought of religion. The nature of God simply precludes the possibility of such a negation at a certain level of truth.

But questions remain: how do I judge such a level has been reached? Do I subsequently accept all religions equally? If so, how do I prevent that from slipping into chaos, given I equate religion with life? Following my earlier line of reasoning, I think that once we change out the faulty epistemology, all becomes a lot clearer. My proposed alternative would be the epistemology given to us by Nāgārjuna. That truth can be demarcated into two yanas or ‘vehicles’ (a ‘conventional’ and an ‘ultimate’) seems simply to follow from the Thomistic ‘real distinction’ between Creator and creation.3 Language and logic both belong to conditioned being, whilst their referent—the transcendental absolute of Truth itself, the Truth which renders all particular truths ‘true’—cannot by its nature be amongst them. What is Real is a Unity that necessarily transcends language, the sacred ‘silence’ that Pseudo-Dionysius, Meister Eckhart, Dōgen Zenji, Lao Tze, Ramana Maharshi and plenty more all concur resides at the top/centre/bottom of all things (depending on your spiritual orienteering…).

As accompaniment to Nāgārjuna, I’ll take the parable of the raft as my guiding myth: the Buddha speaks of the traveller who seeks to cross a river, and forges a raft for himself. Yet when he arrives on the other side, he is faced by a thick forest, and cannot bring the raft with him: he must instead let it float on down the river, going on without it. Already we see an important, if obvious, qualification to any proposed ‘pluralism’. We know that Gautama Buddha was a real religious figure who had his own philosophy of religion; a fairly distinctive one, in fact, being a radical voice in the śramaṇic turn around the 6th century B.C., his teaching becoming one of the heterodox (nāstika) schools of Hinduism. The Buddha began and persisted in his teaching by disagreeing with Hindu philosophy, by insisting on its limitations as a means to nirvāna/moksha, and providing his alternative. Any familiar with his hagiography will also know that soon after his Bodhi Tree enlightenment he travelled around India, debating Brahmins and (so the story goes) proving singularly triumphant. So what the Buddha clearly cannot mean in his parable is there is no such thing as right and wrong when it comes to religious beliefs and practices, because he advocated for his own position over and against those of others. That is, he had his own culturally and doctrinally particular views on how to build a particularly sturdy vessel for your voyage across the river.4

Some might already suggest that this disqualifies Buddhism from holding a ‘pluralistic’ account of religions. In some fashion, probably; but also happily. I have no small distaste for the more ‘liberal’ pluralism which assumes its position simply so as to avoid offending people by suggesting they are wrong. As David Bentley Hart points out, this is more often than not a supreme Western condescension, subsisting on a post-colonial self-righteousness.5 The West takes for itself the role of referee, and softly patronises the world religions by trying to swap their rhetorical swords for balloon animals. There is far more dignity in simply disagreeing, and far less insult to those who simply have different metaphysical views, and will happily argue in favour of them against yours. My contention is never with this.

My reasoning, rather, follows simply from a reflection on the Creator-creation distinction; from that basic parsing of conditioned from unconditioned. The nature of epistemic beliefs—which are only conditioned, contingent, mentally held concerns—is that they are transient, passing, and only come to you because of the configuration of your psychology, physiology, culture, and so on. They are obviously just one part of the conditioned world, and so, as Buddhist and Jain philosophy point out, in a very real way salvation must be found not in them, but beyond them. Thought does not contain God as a particular entity within its midst, as one ‘true concept’ or even the totality of ‘true concepts’ that might comprise a creedal position. Moreover, thought depends upon God as the yet more foundational, unconditioned ground which allows its network of relations. If one responds that religion is not a matter of ‘thinking’ about God, but ‘believing’ in Him, I would gently point out that this already represents a gravitation toward the all-important distinction on which my argument hinges: everything by which we divide the world—which is to say, the intellectual apparatus available to a discerning mind, whether in conscious thinking or a priori faculties—is not capable of encompassing its own Ground. The entire economy of religious meaning—what separates religion from mere history or philosophy—is that it does not merely attempt to systematise a set of true beliefs but gravitates toward that which transcends and grounds those beliefs, a Truth that cannot be exhausted by those beliefs, even if true.

This does not mean that ‘any religion is as good as another’: it means that what ultimately makes a religion ‘good’ or ‘true’ is something that is not that religion, and so a religion’s value cannot ultimately be determined by chavinistic, chest-pounding self-reference. This allows for a normativity that can well be applied to a totality of beliefs and even, when lived, a ‘tradition’. For instance, I take LaVeyan Satanism to be obviously ethically indigent. Its prescriptions of vengeance, pride, and ‘sin’ in general are manifestly stupid, with an abundance of wisdom traditions having pointed out that such traits inevitably lead to ignorance and suffering, assertions coroborrated by lived experience. Real condemnation and judgment can and should occur within the immanent frame.

That can be—and is—true without a compromise of transcendence. Life always ultimately outstrips and exceeds the conditioned language and content that constitutes religion, and thus the latter must finally arrive at a point where it concedes its inability to say what it points to; to touch the fire it dances around. It must come to ‘bow down’ (Q 55:6, Ps. 95:6), as it were, confessing that it does not possess the fullness of truth in itself, but serves only to ‘clear the way’ (Isa. 40:3, Jn. 1:23) for the Ultimate Reality that ‘no vision can encompass’ (Q 6:103), whose ‘ways are not [our] ways’ (Isa. 55:8). This need not be an either/or. Just as we indispensably need certain things in place in our childhood that eventually fall away when we enter adulthood, so too can we speak of very real and substantial metaphysical disagreements that do not ultimately determine the End of our voyage. As such, I would not push my ‘pluralism’ any further than how it already generally stands in Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, and Sikhism—that is, still with a strong and unwavering normativity intact.

WITHIN Hinduism, there is very little taboo surrounding the notion that one ‘chooses’ one’s own deva or devatā depending on the velleity of one’s empirical ego: indeed, it is actively encouraged. The process of encountering one’s iṣṭa-deva(tā) (‘cherished/personal deity’) is absolutely central to any successful bhakti-yoga, and although there is certainly a history of sectarian animosity between, say, Vaishnavas and Shaivas, this flies in the face of an established communal understanding that difference in bhaktic devotion proves no obstacle whatsoever to an encounter with the fullness of God—‘Brahman’, in Vedantic terms—and indeed that the embrace of diversity according to the forms and habits of one’s personal life is a far better cultural vessel for approaching God than anything more rigidly monolithic. I have elsewhere registered my appreciation for, and belief in the necessity of, upaya, or ‘skilful means’ in religion. To edit a favourite Smiths song: some bodies are bigger than others. Some are smaller, some bonier, some wider. No one raft could possibly be presented as dogmatically or doctrinally universal, precisely because the raft itself is always already catered to and—more importantly—fashioned by the one who intends to sit on it.

Pluralists are wont to bring up the fact that the single greatest determining factor in religious allegiance is the place and faith of one’s birth. This is meant to highlight the same ‘historicality’ which the scholar of religion must equally appreciate, and so again problematise the notion of religions as shiny packaged products on the shelves. Here, the ‘choice’ for the Hindu is radically different to the ‘choice’ of the late modern consumer. The former engages in abstraction only where it is appropriate—that is, in the philosophical or logical aspect—and never conflates this with the whole process of choosing: which means, vitally, that one never ultimately creates an essential dualism between deva and devotee. The deva is supposed to be a spiritual guide, a guru, somtimes in a not dissimilar fashion to how a therapist proves a psychological guide for their client: but in this case, this is a guide toward union between ‘master’ and ‘student’. One begins with an acknowledgement of one’s embeddedness within a cultural and mental milieu, and tries to find the Truth through that, precisely because one already believes that an ultimate horizon of Truth (Sat, Brahman) is accessible in the immediacy of any lived experience.

All this follows from a simple belief in real transcendence, because from that comes a recognition of the ubiquity of the Divine in conditioned circumstances. The common error we make is, predictably, the essentialisation of borders. If God really is the Being of all beings, then all the ‘being’ that we are and do must, insofar as it is not clouded by sin, be revelatory of God. That applies wherever we stand, in whichever nation, epoch, or tradition, and whatever cognitive beliefs and propositions we are exposed to and/or accept. Hence why Shashti Tharoor can congratulate a Christian on possessing a view generally compatible with Hinduism: Christians are drawn to the deva of a pious prophet crucified like a common criminal, who then tramples on death in glorious resurrection. If one is entranced by this as the vision of God that evokes the most love (bhakti), then it is ‘true’ insofar as it reveals the Truth most clearly for that particular devotee. The notion that it might then be set over and against other devas as immeasurably ‘better’ or ‘true’ in contrast with their ‘falsity’ would be absurd.

That this might be accused by Abrahamic faiths of pandering to a supposed ‘customer’ rather than obliging the believer to comport themselves to a new tradition is only a show of ignorance. Recalling Aquinas and Gregory on the subject of human desire: when people become (for instance) Christians or Muslims, it is because they are drawn to these faiths out of a personal desire. This is not a desire that falls from the sky, but arises from lived experience: the child of lax parents and decadent culture might well find appeal in the ritual strictures of Islamic dietary law or jurisprudence (fiqh) as a reaction against this upbringing. At no point does this desire cease to be facilitated and produced by its environment. Yes, Augustine equates the gravitation to faith with ‘grace’: I do not disagree with this at all, so long as we understand this is a grace that manifests within and through the cultural and psychological conditions of that individual, and so clearly embraces a pluralism of its own insofar as it leads people to God in cultures with limited or no Christianity. The same factors that conditioned and kindled my young affection for the poetry of T.S. Eliot (mainly a sense of distant, yearning teenage lugubriosity) also contribute deeply to my appreciation for Anglo-Catholicism. I know that had I lived differently (less self-enforced, melodramatic solitude, perhaps…) then my corresponding love for the art might be diminished or altogether absent, and so too my denominational preference. This is one of the greatest errors in the discussion of aesthetics in philosophy, it seems: one mistakes the variety of Beauty’s manifestations for its relativism, when it should instead signify its transcendence. We find beauty through personal feelings and dispositions, a numinous attraction which draws us without rationale or utility, always embracing determinate form in its manifestation but never thereby necessitating preclusion of others; indeed, forever reappearing in novel forms in an endless play (lila) of infinite wonder.

That assertion—that in the realisation of an ultimate fullness there will still be a distinctive pattern—might surprise some, but it is the second vital element of the pluralism I advocate for here. Monism is not holism. But to any who might try to pounce on it to establish a negation, to assert that this distinctiveness gives priority to ‘my’ tradition, not ‘yours’, I would advise pause. I simply see no feasible justification for the preclusion of alternative traditions on these grounds. It seems much like suggesting that for beauty to be realised in an infinite degree, it would have to be confined exclusively to a single work or genre of art. Not only is this a ridiculous proposition, it’s contradictory: surely a true motion to plumb the depths of beauty would entail the full embrace of a polyphony of aesthetic mediums. Something different of beauty is told in a Beethoven concerto, a Cézanne still life, or simply a sunset in a Target car park (these are always the most resplendent). To deprive ourselves of these on account of their presupposed competition is surely madness. After all, a Rembrandt cannot be opposed to a Raphael in the way that A is necessarily opposed to ~A. I cannot conceive of any persuasive argument that would attempt to confine the difference in religious ‘livelihood’ to the latter rather than the former. If this were true, then you would also have to be of the opinion (and, frighteningly, some people actually are) that an ideal world would be one in which the diversity of religions would be drawn together under a single formal mantle; their various distinctions extirpated in favour of a Procrustean homogeneity.

For an integralist, that is, with their real commitment to setting all world religions off against Roman Catholicism—a Catholicism absolutely historically grounded in European culture and history—the nation of India would ultimately have to be hollowed of its indigenous vibrancy in order to conform to, and fall within, the borders of a supposed monolith of the Church. Encountering the Shaiva’s devotion at a Jyotirliṅga, her utterance of the Panchakshara mantra, her delighted celebration of the divine dance (tandava) and overcoming of darkness in the annual festival of Mahāśivarātri, one would have no choice but to consider them inherently inferior, and so—for the sake of full salvation/revelation—in need of colonisation; needing to be wiped clean in favour of say, a eucharistic idiom, perhaps with the distant, faintly plaintive choral piety of the Tridentine rite, maybe accompanied by the lofty frills and arabesques of a Baroque aesthetic. The symbolic resonances of the lingam, with its very intention of directing the devotee to the realisation of Shiva in and through all the diversity of creation (rather than being pinned to one culture, idea, or manifestation) must ultimately come to heel at the beck of Vatican authority. The embodied experience of matted hair grown long, or the tripundra smeared thick on the forehead, or the yogi contorting his feet above his head in some extreme āsana are ultimately set against the Catholic symbolic economy, all on account of the belief that the latter must be in some sense ‘ultimate’ and that one must belong to that Christian tradition—with all its particular rites and acceptations—in order to have access to the ‘Ultimate Truth’. As one especially repugnant integralist motto goes: error non habet ius (‘error has no rights’).

If I may venture to sweeping proclamation: I do believe that almost the entirety of religion in its manifest form is oriented toward the embrace of created diversity rather than its diminishment. The difference between nirguna brahman and saguna brahman, between apophatic and cataphatic theology, between perhaps even the dharmakāya and the nirmāṇakāya is that in each case the latter is not merely a bridge to but an expression of the former in and as creation. If the development in Vedanta from Śaṅkara to Madhvā has any truth, it is in the revelation that one cannot relate to God without love; that we as persons must respond to the Infinite in the mode of personhood if we are to truly understand both ourselves and it. And this form of ‘relational’ devotion, finally in the relation we have to our iṣṭa-deva but also in the various rites, sacraments, and theologies we adopt in our traditions, simply cannot be subject to the binary of logical affirmation or negation. To ask whether one religion or another is ‘the true path to God’ at this level is about as sensible as asking whether football or rugby is the ‘true sport’.

Or better, we can realise that we need not reach for analogy at all. To insist on an exclusivism of religious devotion is really a matter of insisting that all lovers must abandon their beloved because you believe that their love is ‘inadequate’ or ‘incomplete’ in comparison with your beloved. When Hindu devotees—and indeed all religious people, I truly believe—find their iṣṭa-deva, they are first and foremost finding someone with whom they would like to fall in love. Whichever figure evokes the greatest love for you is the figure who will most fully reveal Love itself, the fullness of Being, which is infinitely present in all things if only we have eyes to see. Two things can thus be true at once: you would never dream of exchanging your beloved for another, even whilst acknowledging from afar that someone might find the same depth of love in a wholly different person. Determinate form is not lost: indeed, it should be embraced without reserve, and so reveal an endless ecstasy of devotion and bliss, because it is precisely your love, in their specificity and personhood, which makes them loveable. But it is a mean and meagre affection that would see one come up from this devotional plunge with bitter words of exclusivity and supremacy, and a bizarre insistence that the whole world come to their own lover, rather than freely and happily knowing a love of their own.

SO my final position6 is one whereby I think it possible to have three cakes and eat them all too: we have 1) true transcendence, which causes pluralism in the first place, yet we do not relinquish but instead embolden both 2) normativity and 3) determinate form. For all my abstruse language, this is really just what love is. An attraction that draws conditioned, determinate persons to conditioned, determinate persons, simultaneously entertaining devotion only to one’s own beloved without ever thinking this entails a preclusion of the possibility of other loves for other people. And so it is that we find ourselves, in love, in a strange state of glorious, blissful surrender.

Love is, after all, vulnerability; it is self-exposure before another, a willingess to come down from our ivory towers and defences, our carefully-wrought cages established to protect ourselves from the slings and arrows of a cruel world, to acerbically gather all that we can under our control to prevent the unwanted from ever meeting us again. We must come undone in love, give over our wills and our attachments, and to say, in the words of Mary, ‘Let it be unto me according to thy word’ (Lk. 1:38). True love, I contend, assumes a figure directly opposed to exclusivism. It seems necessary to concede that any claim to the ‘Truth’ by a given tradition must be a claim that is finally self-opening, finally ‘kenotic’, as Christian theology would have it. That is, a real orientation toward Truth is typified not by a kind of outward expansion of a given bailiwick, whether purely epistemic or accompanied by a real colonialism, but the antithesis: a deliquescence of the fixity of self-identity, an ultimately radical openness and creedal commitment to seeing the Truth in other traditions rather than asserting what one believes the Truth is and then attempting to claw all other patterns of living under its scope, which is what the inclusivist is at risk of doing.

Which—to prove that this was not all a wild goose chase—is why we can return to the question of ‘teloi’. The consumerist picture of religions presumes that one must be selected over and against the others, that we are in a competition from the very first, one where winners and losers must be present for the game to work at all. Yet what can a ‘victory’ in this paradigm actually resemble if not yet another tribal conquest, reinforcing an ethics of violence and dominion rather than peace and compassion, those virtues whereby Unity actually becomes manifest? So I return to that inner ‘silence’ at the heart of things, and again to the Buddha’s raft, which is not itself the Shore. Although, yes, there are real metaphysical debates to be had, it is also the case that any ‘victory’ is located only in ‘humility’. All true dogma and doctrine point beyond themselves whilst in some way participating in that to which they point: as such, the realisation of their telos must entail not the ossifying of that dogma into yet more intransigent forms of monolithic, monochrome dominance, but rather its ‘loosening’, a gradual cessation of paranoia about ‘being right’ as one slips into a state of non-attachment (vairāgya) which pervades one’s life so wholly that it applies even to one’s beliefs about Ultimate Reality. Whilst the Desert Fathers averred that the inner aim of the ascetic life was to cultivate an attitude of ‘apatheia’ to the habits and passions of embodied experience, this attitude cannot stop there: it must be extended to the content of religious doctrine itself.

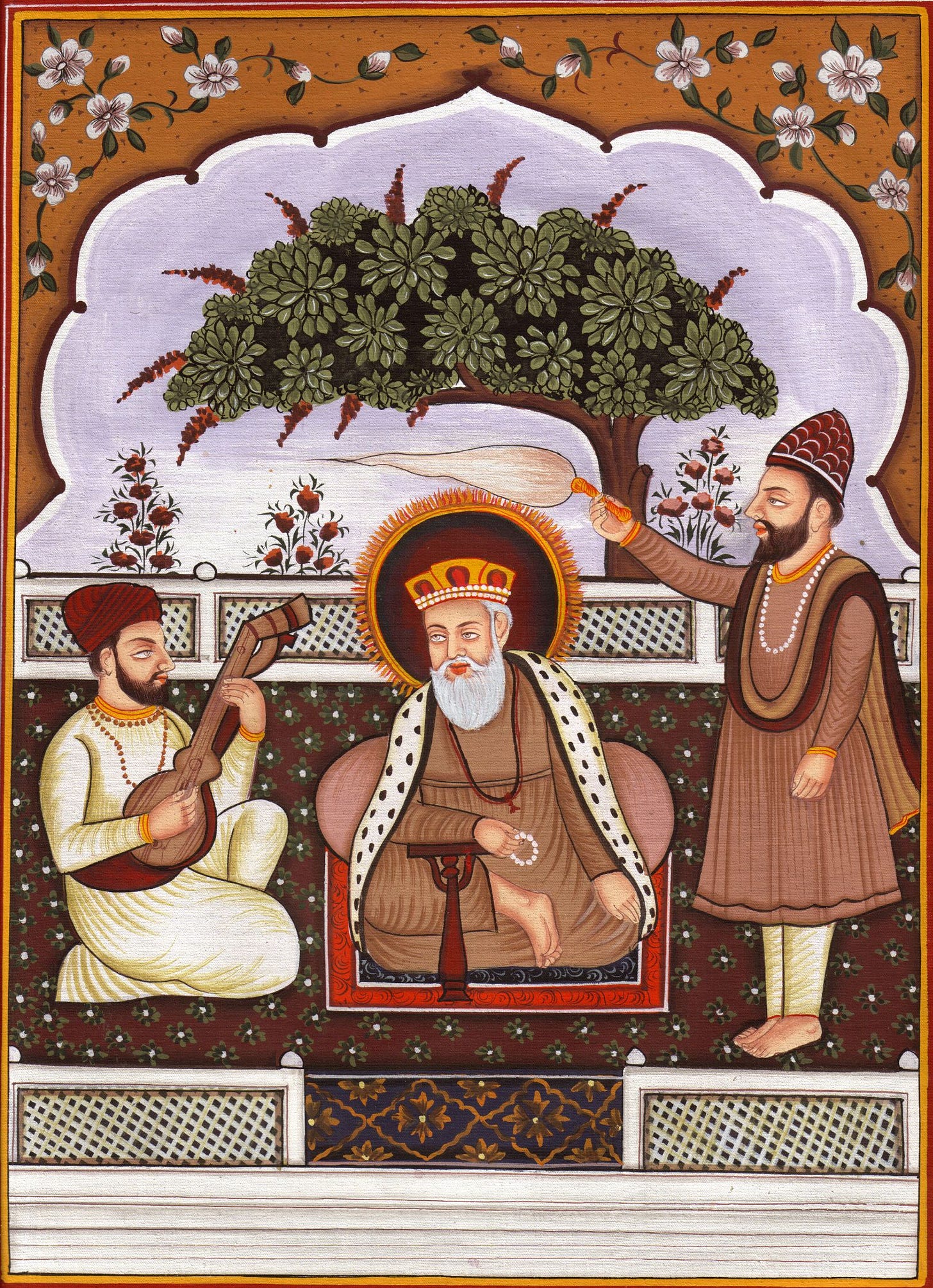

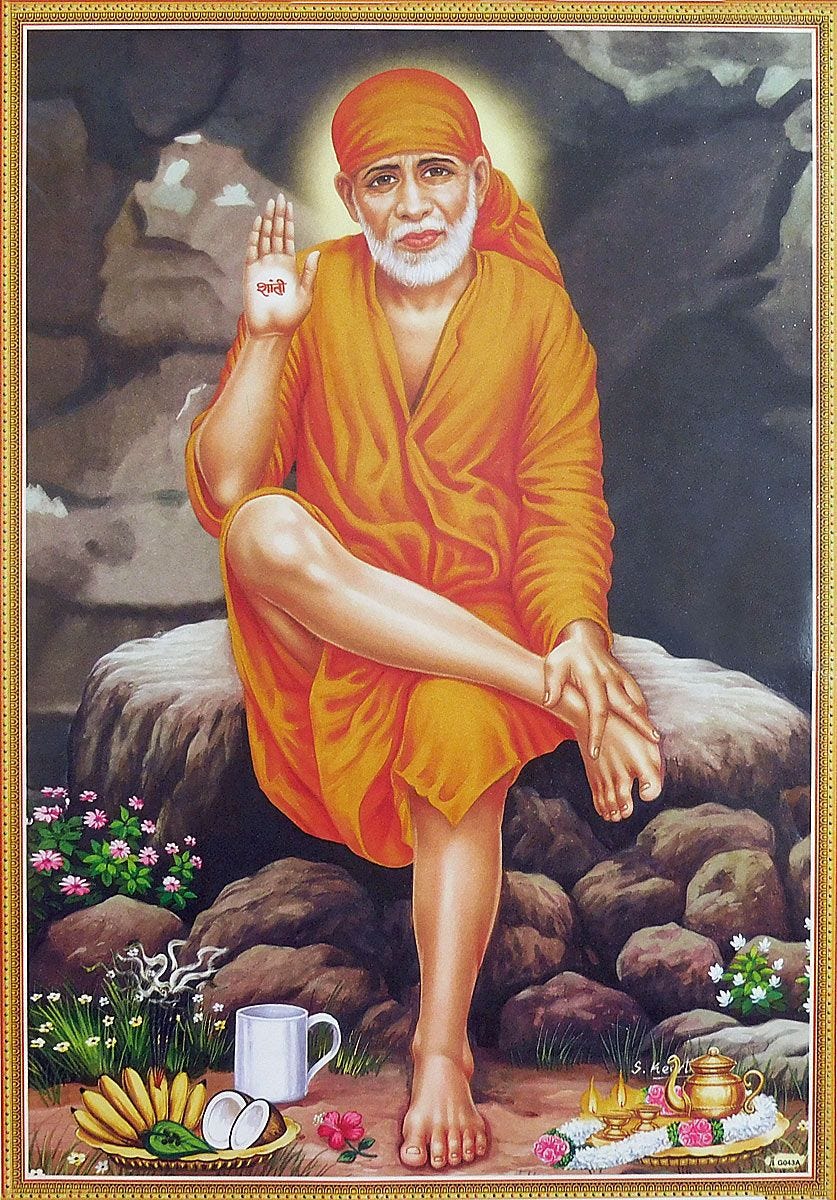

There is a certain genre of Indian mystic, in fact—to which the likes of Sai Baba, Kabir, and Guru Nanak all belong—which has mastered non-attachment in a way that results in an almost necessarily syncretistic religious life. As

has pointed out, at the upper echelons of religious consciousness we encounter something like the archetype of the Holy Fool; one who stumbles blindly over the boundaries of human distinction, giddy on the inebriation of infinite, mystical love, no longer beholden to the sobriety of worldly distinction and logic. It is this that I—tentatively, humbly—wish to adumbrate as a potential form for future religious revelation and tradition: for ‘apocalypse’.7 Ibn’ Arabi follows this mould, and as such can, whilst remaining fervently and absolutely a Muslim, make a proclamation like the following:Do not attach yourself to any particular creed so exclusively that you disbelieve all the rest; otherwise you will lose much good, nay, you will fail to recognise the real truth of the matter. God, the ominpresent and ominpotent, is not limited by any one creed, for, he says, ‘Wheresoever ye turn, there is the face of Allah’ [Q 2:109]. Everyone praises what he believes; his god is his own creature, and in praising it he praises himself. Consequently he blames the beliefs of others, which he would not do if he were just, but his dislike is based on ignorance.8

There must be a certain measure by which we come to assess our lives and dogmas, to intuitively discern what to keep and what to leave behind as we move onward (historically) and upward (spiritually) as a species, even if we readily acknowledge our vast imperfection in this process of discernment. And I think the only viable candidate for that measure is Unity. Just the same way that individuals can labour under a misapprehension that opaques Reality—such as a conviction that they are exclusively disposed to the Truth whilst others are labouring in ignorance—so too can this affect communities, cultures, and whole civilisations, and requires real assessment in order to allow for betterment.

As such, I think it perfectly appropriate to measure the fullness of a tradition’s revelation by the extent to which it is able to practice non-attachment. For the Abrahamic faiths, in their formulations en masse, this may seem depressingly distant. But it’s clearly not impossible: we see other traditions (and I will exult Sikhism in particular) that are happily syncretistic, and find this to be no contradiction—indeed, an augmentation—of their revelation. The fervent and typically violent clinging to dogma, in Jain terminology ‘ekāntavāda’, or ‘one-sidedness’, is seen as an obvious impediment to spiritual development. At the revelation that even our sacred beliefs are mutable and conditioned, either we grit our teeth and cling to them with ever more ferocity, thus surely resulting in suffering, or we have the courage to let them go; to give them up to God, just as we would any other worldly attachment. It seems to me obvious which is a greater show of devotion and spiritual truth. When it is agreed that God is not a proposition, or a doctrine, or an idea, but is the ground and source of such things, necessarily transcendent of them, surely true devotion would result in the relinquishment of those things for the sake of God; the offering even of our dearest beliefs at his altar, just as Abraham gave up his dearest in faith—and, let us not forget, received it back in grace.

Just as I have warded off any association with ‘liberal’ pluralism, so too must I abjure any acquaintance with perennialism. My claims here should by no means resemble a recommendation to abandon ‘formal’ religion. As I say above, I do not think this is possible, and even mystics who did something like it (such as Sai Baba, for instance) were still irrevocably grounded in their cultural traditions, albeit very syncretistically. The best one can do is rock the boat, but not hop out altogether. Nor should one want to. To venture toward an esoteric tradition that supposedly grasps the mysteries to which all other traditions merely feebly gesture would be to miss the point entirely, slipping into the same reification of God that we are originally trying to escape in the exclusivists. The last thing a pluralist should ever prescribe is the mixture of all religions into a hazy, globulous, green-grey soup, or an attempt to soar past them on the wings of a superior understanding. One must be in one’s tradition.

In that vein—to prove that I am still very serious about immanent difference—this is why I think Christianity (my religion, if you weren’t aware) is especially well, even uniquely, disposed to such an attitude; why I would choose and have chosen my Christianity over other world religions. Its very central claim is that God’s love was so immense that he abandoned his own infinite majesty in order to take the form of a frail, vulnerable, mortal child, then to teach peace, compassion, and justice, and finally to willingly accept agonising death in forgiving sympathy with his killers. Many theologians have noted this ‘kenotic’ self-givenness as an instance of supremely compassionate love; far too few have noted that it is surely a pattern that must be emulated in our own sense of conviction and rightness. We cling out of fear, above all. Yet the Christian narrative tells us that love—and eternal life—reside not in the clinging, not in keeping God as God and humanity as humanity, ferociously tightening our grip on our own identities. It resides in letting go, and discovering grace in our self-emptying.9

It is there that we find that ever elusive, ever present silence at the centre of things. A silence not of occupiable space, upon which we might construct a new or esoteric tradition (as the perennialist would have it), but a silence in which all spaces exist, moving invisibly through each and every tradition because it moves invisibly through each and every life. The classic Chan image remains apposite: religion is ultimately nothing but a finger pointing at the moon. The Source whence both reality and religion (and in an ideal world those two words would be synonymous) come and to which they are returning cannot be exhausted, only fully realised, in particularity and difference. And I long and hope for that realisation. But for all the very real specificity of our cults and rites and the logical priority we might give to our metaphysics, I have a creeping suspicion that when their End—that Truth to which each lay special and unique claim—is manifest ‘all in all’ (1 Cor. 15:13), we may well find it reveals that we are, and always have been, One.

How futile to sit in contemplation,

like a stork with both eyes closed.

While trying to bathe in the seven seas,

we lose this world and the next.

How futile to sink in misdeeds,

we only waste away our life.

I tell the truth, do listen to me,

they alone who love, find the Beloved.

Some worship stones, some bear them on their heads;

some wear phalluses around their necks.

Some claim to see the One in the south;

some bow their heads to the west.

Some worship idols, some images of animals;

some run to worship the dead and their graves.

The entire world is lost in false ritual;

none knows the mystery of the Almighty One.

Savayye 9-10

William H. Harrison, In Praise of Mixed Religion: The Syncretism Solution in a Multifaith World (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2014), 3.

De mortuis non esse delendum. Quoted in Morwenna Ludlow, Universal Salvation: Eschatology in the Thought of Gregory of Nyssa and Karl Rahner (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 57.

See the particularly famous bhasya on Nāgārjuna’s most famous text: Rje Tsong Khapa, Ocean of Reasoning: A Great Commentary on Nāgārjuna’s Mūlamadhyamakakārikā, trans. Gheshe Ngawang Samten and Jay L. Garfield (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 26.

Or, if we are being more faithful to the parable, the Buddha actually had no need of a raft whatsoever, but could teleport across the river at will. But we’ll leave that for now.

David Bentley Hart, Theological Territories: A David Bentley Hart Digest (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2020), 50.

Until someone far smarter than me comes along and changes my mind completely, of course.

In one sense, our apocalyptic imaginations might aspire to this sort of religious mind historically, by taking note of the remarkable consistency in religious evolution: local animisms, then differing polytheisms, then competing monolatries, then monotheisms, and finally unifying monisms. So we might, and should, hope that this kinds of mysticism may become increasingly normalised and sought in popular faith. But although ‘apocalypse’ must certainly maintain a thoroughly chronological orientation, it would be a failure of apocalyptic thinking to suppose that it could be measured in exclusively historical developments of ‘religious consciousness’ in generally Hegelian fashion. That which consciousness directs us toward, after all, is an Absolute Present which we by nature always already are; and in history we see many ages which vacillate between degrees of greater or lesser spirituality, rather than a steady, gradual ascent. Ours, of course, is especially dire in this respect. As such, our telos is not something that history might somehow ‘arrive at’, at least not exclusively, because one cannot ‘arrive’ at a present that is always already the case: or at least, this ‘arrival’ must be merely preliminary. God awakes from his dream not in the timeframe of that dream, but in his own Presence.

See Karen Armstrong, Twelve Steps to a Compassionate Life (New York: Anchor Books, 2011), 155.

However, I also think that the singularity of Christianity’s claims proves the greatest ‘trouble’ to this pluralistic question, and so I envisage having to make a post specifically dedicated to how the views I have set out here cohere under the aegis of Christian doctrine.

Wonderfully written my friend, there is much to contemplate here. If my gentle pushback contributed in anyway to this erudite and thoughtful piece, then I am happy.

A couple of quick thoughts:

I fully accept that grace erupts from within at the same time as arriving from without - it has to be this way of course. I just wonder whether you make too much of the inevitability of grace arising from the particular contingencies of our life - I’m thinking of CS Lewis talk of being a reluctant convert. Did his life, his childhood, his academic pursuits, result in his certain conversion? History and contingency can work against grace just as much for it, it seems to me.

Regarding the vision of unity in diversity you seek, I wonder whether or not it is enough to posit the Christian understanding of the Trinity (with all the qualifications something like Hart’s Vedantic construal allows) as one way of underwriting this. Are there other ways? (I’m genuinely asking). Reading Philo and Ibn Arabi, albeit as a Christian, whilst of course neither writers endorse a full blown Nicean trinitarianism, the very fact of creation leads both - it seems to me anyway - to endorse something like a diversity and unity within God. For example, the latter refers to “Nafas al-Rah-mãn” the sighing of God which grounds all of creation. Henry Corbin, a scholar of Ibn Arabi writes, “For the cloud (the sigh) is the Creator, since it is the Sigh He exhales…”. If this isn’t a straining towards what is later fleshed across the earlier ecumenical councils, I’m not sure what is.

I look forward to conversing with you in person on the completion of your first term.

Peace and all good.

Much rich contemplation here on the religion of the future. I had not thought to describe the mystic, as you do here, as the Holy Fool, but you’re certainly right that that’s what they are.